|

History

of Oldbury, Langley and Warley

|

||

|

Communities

of the West Midlands

|

||

|

The

website of Langley Local History Society - Oldbury Local History

Group - Old Warley Local History Society

|

||

|

||

| HOME | |

| NEWS & EVENTS | |

| HISTORY SOCIETIES | |

| PUBLICATIONS | |

| GALLERY | |

| QUESTIONS | |

|

article 003 OLDBURY COURT HOUSE AND PRISON |

|

Oldbury 'Court of Requests' A 'Court of Requests' was established in the early nineteenth century to deal with debtors. It could rule on cases up to £5 in value and impose terms of imprisonment up to 100 days. The court was estabished through an Act of Parliament in 1807 promoted by Lord Lyttleton, the local MP, 'for the more speedy recovery of debts within the parishes of Halesowen, Rowley Regis, Harborne, West Bromwich, Tipton and the manor of Bradley'. Oldbury was part of Halesowen at the time, and a relatively small and poorly developed settlement. Despite larger towns being within the area covered, Oldbury was chosen for the siting of the new Court. The first court was held on 19th May 1807 with Thomas Turner as Chairman, Ellis Sutton as Clerk of the Court and Thomas Johnson as Sergeant of the Court, although the records do not show where it was held. The Revd L Booker, Vicar of Dudley, preached an 'excellent sermon' in Oldbury Chapel on the day the Court opened. The Court asked that it might be printed for 'the restraint of dissipation and vice, the encouragement of frugality and virtue, and the universal diffusion of prosperity and happiness'. Lord Lyttleton was presented with a silver cup to mark his services in obtaining the Act of Parliament. Appropriate hats were soon provided for the court officers, one with a gold band for the Sergeant of the Court, Thomas Johnson, and one with merely a black band for his assistant, John Turner. In July 1807 the Court approached the Lord of Oldbury Manor, Francis Parrott, to sell them some land in Church Street to establish the new courthouse and jail. He agreed, but the Courthouse was not opened until 1816. Meanwhile, the work of the court proceeded. The fines for contempt received by the end of 1807 were distributed to the poor of Halesowen, Harborne and Oldbury. Those levied for 'insulting and obstructing officers of the court' were paid in January 1810 to Joseph Wright, the Treasurer of the recently established Oldbury Sunday Schools, to benefit the Sunday Schools movement. This amounted to £11 13s 4d, no mean sum at the time, and suggests a substantial amount of insult and obstruction on the part of the local citizens to the new court. The Sergeant, Thomas Johnson, seems to have performed his duties with vigour, for the Court minutes record that he was ordered to pay £1 1s in recompense for injury to James Walker following a complaint against him, and to 'make confession of his conduct'. Further complaints about Sergeant Johnson followed, and he was finally discharged on 30th April 1811. Another officer of the court, John Turner, reported that he had observed goods being removed by night from a house, presumably goods that the court had ordered to be seized for debt, or ones in a case about to come before the court. The minutes record him saying to the woman carrying items from a house, "You are removing your goods in time!". She answered, "Ah, damn you, you stripped the house once of all the goods, and we will take care you shall not again". In October 1811, a Birmingham basket maker, Stephen Porter, was present in court and interrupted proceedings. He 'did there and then make use of insulting language before the Commissioners sitting in Court … and continued to do so after being admonished'. The Commissioners ordered him to be removed, and he later took action against Revd David Lewis, the Anglican Minister at Oldbury, who was probably chairing the Commissioners. Tthe minutes record that Revd Lewis incurred considerable expense in defending the action, and the court agreed to pay these costs from Court funds. These events suggest that the court was somewhat 'ad-hoc' in its approach and faced difficulties in establishing its authority.

The courthouse and prison

It is likely that public houses were used for much of the court's initial work, including the 'Swan Inn' at West Bromwich, where a special meeting was held in 1809 to fill vacancies in the list of the Court Commissioners. Finally, in 1815 the builders William Harris and Thomas Whitehouse were asked to provide a plan and estimate for the construction of the courthouse and prison, and these were completed in 1816, presumably by them. Operations were tightened up in the new premises, and the prison regime was quite severe. In July 1820 it was ordered that 'no kinds of provisions, ale, spirits, or drinkables be allowed to be received or taken into the prisoners for their use of any description whatever, except a loaf of bread weighing 1lb for each person per day'. In contrast, however, in May that year they had made the sensible ruling that working tools should be taken in distraint for debt only as a last resort when sufficient other goods could not be seized. By 1828, John Horton was employed as the Sergeant to the Court. On 31st March that year, when a little drunk he decided to confront the notorious 31-year old collier William Steventon, known as 'Billy Sugar', who had outstanding warrants for debt against him. Steventon was known as a man of vicious character who often carried a knife to resist attempts to arrest him. Sergeant Horton challenged him at 'The Whimsey Inn', Churchbridge, and said he was under arrest. Steventon, who was on his way from work, asked for time to go home to wash and Sergeant Horton allowed him to do so. When Billy Sugar returned to the inn, he had a large knife with him, and stabbed Sergeant Horton fatally. He made his escape, but was soon was arrested. He was sent to Shropshire assizes and sentenced to be hanged. His public execution in August, along with two other murderers, was attended by a crowd of about 5000. His body was passed to Salop Infirmary for dissection.

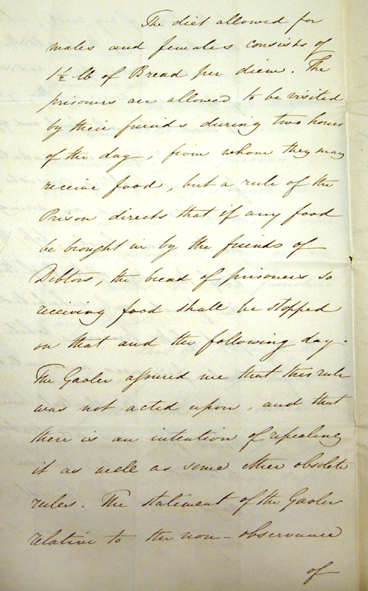

The Court of Requests gaol had cells for men and women prisoners. In 1839 the 'Master' was Henry Parrish and the 'Matron' Mrs S Martin. At this time the Court met fortnightly on Tuesdays, with William Caldicott as the Clerk and Collector. At the census of 6th June 1841, the 'Resident Gaoler' was John Mason, and his wife Mary was the 'Matron'. They had living accommodation at the courthouse, together with their daughter, Mary Anne, and a domestic servant Elizabeth Carter. The gaol itself held one woman prisoner and nineteen men. Their ages ranged from 20 to 60, two-thirds of whom were iover 40. Only five of the prisoners are recorded as being born 'In County', which would be Shropshire, suggesting that many of them were either migrants into the area or hailed from those parts of the court's jurisdiction in Staffordshire. They were drawn from several occupations, all hard working, low paid jobs: eight were coal miners, two were brickmakers, two nailors, and one each of boatman, caster, chainmaker, cooper, cordwainer, (h)ingemaker, and pot turner. The prison conditions were very bad by the 1840s, and an inquiry was ordered by the Home Secretary. This was carried out by John G Perry, Inspector of Prisoners, who reported to Sir James Graham in 1844:

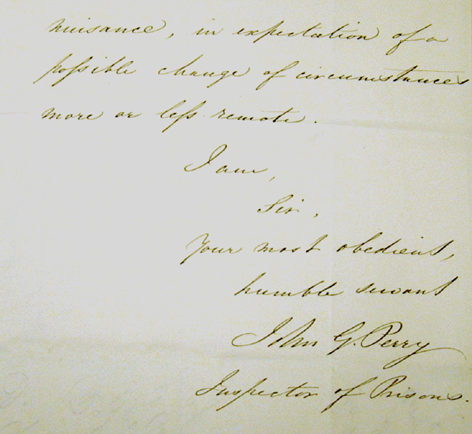

His

final paragraph makes clear his condemnation of the Oldbury Commissioners

in not improving the prison: "In reply to this position, I am

bound to express my opinion that with the means in their hands of

improving the Condition of the wretched inmates of the Prison, the

Commissioners are not warranted in delaying the abatement of an

admitted nuisance, in expectation of a possible change in circumstances

more or less remote."

The County Court and the Magistrates Court In 1846 the 1807 legislation was repealed by the new County Courts Act. Oldbury became part of Circuit 25, and County Courts were held monthly in Oldbury Courthouse. The area covered comprised Oldbury, Langley, Warley Salop, Warley Wigorn, Smethwick and West Bromwich. The First County Court judge was Nathaniel Richard Clarke, with Joseph Heapy Watson as Clerk and Charles George Megevan as High Bailiff. Clerks to the Court House and Session Court were the Oldbury solicitors Hayes & Sons. The prison report was not ignored, and by 1850 Slater's Directory reported that the Court House was recently improved and now 'a neat and commodious building'. It even contained 'apartments for the magistrates who assembled in petty session every fortnight, and for the judge in the county court, who sits monthly to determine causes of any amount not exceeding £20.' Five years later two assistant clerks were listed, J B Baly and George Wheatcroft, so the work of the courts was probably expanding as the population of the area grew rapidly. In 1858 West Bromwich leaders initiated moves to have the County Court transferred to them. However, strong opposition fought off the challenge, the court was retained at Oldbury, and the government even paid £3000 to extend the court buildings. This reprieve was not to last, and in 1889 West Bromwich, by then a County Borough, was successful in having the County Court transferred to it. The magistrates' court remained in Oldbury and continued to operate at the courthouse. Littlebury's directory of 1873 shows that none of the twelve magistrates actually lived in the district, although several had industrial interests in the town. The premises were eventually bought by Worcestershire County Council, and the Police Station moved into it just in 1904. They occupied the ground floor with the court room above. The magistrates for Oldbury Petty Sessions, covering Oldbury, Langley, Rounds Green and Warley, continued to meet each Tuesday at the courthouse. By the early 1900s, the magistrates were almost exclusively drawn from the ranks of local industrialists, with G S Albright, S Bennitt, A M Chance, W E Chance, E Danks, J W Wilson, and J E Wilson among them.

See more recent pictures here.

Crime and Punishment The procedings of the magistrates court were reported regularly in the 'Oldbury Weekly News' and the 'Midland Chronicle', and record the domestic and illegal activities of the people of Oldbury. Domestic disputes featured regularly with drunken husbands becoming violent, brothers falling out and coming to blows and neighbours fighting over disagreements. Men and women are summoned for drunkenness and foul language on the streets. Wartime brought its own peculiar offences. A surprising number of employees in the munitions factories of WW1 were brought before the court for the recklessly suicidal offence of possessing matches or smoking materials within the factory. Lighting restrictions saw men and women before the court for willfully or accidently 'showing a light'.

Sources The main sources for this article were: F W Hackwood, 'Oldbury and Round About', (1915), Whitehead Bros and Cornish Brothers, pp196-202. Hackwood quotes the details recorded in an article in the 'Midland Chronicle' , 22 August 1913, p6. The killing of John Horton is described in an article by Bob Taylor in 'The Bugle Annual, 1981', pp 89-90 'Report on Prison the Oldbury Court of Requests', 24th June 1944, by J G Perry, is document HO45 - 778 in the National Archives. Details of wardens, prisoners, magistrates etc are taken from various directories dated 1840 - 1904, from the 1841 Census, and from Bone's '1905 Yearbook' for Oldbury

Postscript The magistrates have moved into new modern buildings in Low Town, and the police have left too. The Courthouse building now houses Oldbury Library on the ground floor. The court itself still remains on the second floor, used as a storage space for council documents and papers. It still has the court fittings with the dock, the witness box and the magistrates' bench, and its one fireplace, strategically placed behind the bench to keep the magistrates warm. The police cells also remain, substantially intact, but again used as a store for old papers. The court fittings are still intact and should be retained. These are buildings that must be preserved since they represent an important stage in Oldbury's social development, and they are worthy of a better use than just being a store room for unwanted papers. With the expected move of the Public Library to new building in the next couple of years, a new sympathetic use for the whole complex is required, preferably one that allows the fittings and fabric to be retained.

This article © Dr Terry Daniels 2008 - contact for permission to use extracts

|

||||||||||||||||